Andrew Draper reports from the European Sustainable Energy Week on efforts at the European level to make the battery value chain more resilient. More work has to be done to plug huge gaps between market supply and demand, and skills.

Making the European battery chain more resilient, indeed future-proof, relies on training 800,000 people and providing them with battery-specific expertise before 2030, according to Vincent Berrutto of the European Commission.

Speaking at a session of the annual European Sustainable Energy Week (EUSEW) in Brussels in September, Berrutto said a lack of skills represents a “real barrier” to the future development of the European battery value chain. He is head of unit in the Directorate-General for Energy.

He said the European battery market is buoyant and growing, and the need for batteries will become ever more important in the energy landscape. “We need a strong manufacturing sector to create jobs and growth in Europe and make sure we reduce energy dependency on imported products,” he said. There has been “big progress” in battery technology in Europe, but several challenges remain to be overcome, he added.

He said 2021 was another record year for the deployment of stationary batteries and EVs (1.7 million new EVs sold = 18% market share). Lithium batteries still mostly came from Asian manufacturers based in the EU, but gigafactories are being set up in Europe, especially in Sweden and Germany. That trend will mean a growing market share in Europe, he said.

The average global battery price fell 6% last year but the trend now, with the rising cost of materials, is that battery packs may be at least 15% more expensive in 2022 than the year before. In 2030, demand for stationary batteries could be double what was forecast two years ago, he said.

Upstream raw materials

“One area that remains very challenging is the upstream raw materials segment, which is the least resilient of the battery value chain,” he said. “And so that is an area where we spent more effort. The supply gap for battery raw materials increased in 2021. Currently, batteries are mostly sent to Asia for recycling.”

Berrutto pointed to Northvolt of Sweden as a success story. It makes battery systems and cells and, since being founded in 2016, has secured more than $55 billion worth of contracts. Key customers include BMW, Fluence, Scania, Volkswagen, Volvo Cars and Polestar. It is developing recycling capabilities to enable half of all its raw material requirements to be sourced from recycled batteries by 2030. “They claim they produced the first battery made from 100% recycled nickel, manganese and cobalt,” said Berrutto. “…With a European effort, that shows we can make a real difference.”

“But a lack of skills risks being a significant barrier to investments…800,000 workers will need to be trained and equipped with battery-specific expertise across the battery value chain well before 2030. That’s a major issue”

He believes the European Battery Alliance (EBA), set up in 2017 by the Commission, national governments, industry, and scientific community, is on track to meet its objectives. The alliance has attracted the industrial participation of some 750 actors and more than €900 million in funding from the EU’s Horizon Europe funding programme for R&I.

At inception, European battery cell manufacturing had no significant scale, it accounted for only around 3% of the world market and faced a future dependent on foreign suppliers. The EU expects production in the EU will match demand by 2025. Production will rely on the successful recruitment of the necessary skilled workforce, however.

The EBA aims to develop an innovative, competitive and sustainable battery value chain in Europe. It brings together EU national authorities, regions, industry research institutes and other stakeholders in the battery value chain.

Berrutto pointed to common projects under IPCEI (Important Projects of Common European Interest). A two-part IPCEI has been implemented to promote battery production: the IPCEI on Batteries and the IPCEI European Battery Innovation (EuBatIn). Under both programmes, participants represent the complete value chain, from materials and cells to battery systems and recycling. A €6.1 billion programme of funding has been established by 12 member states, with a further €14 billion of private-sector investment.

The projects have several working areas, including raw materials, cells/modules, battery systems and recycling. For example, under the programme, BASF has a new plant producing cathode active materials (CAM) in Schwarzheide, Germany. The project also includes intensive research for specific product properties and efficient recycling. BASF is planning a battery recycling black mass plant in Schwarzheide as well.

Berrutto said the EU is about to announce a plan for the digitalisation of the energy sector. The aim is to use digitalisation to reduce energy consumption and increase the use of renewables in the energy mix. This includes the increase in the bi-directional charging of EVs.

Wide supply and demand gap

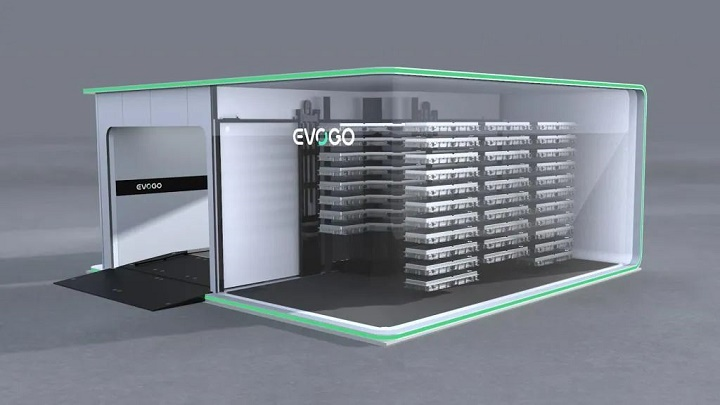

Thore Sekkenes, programme director of the EBA, said his organisation knows of 50 cell-manufacturing facilities in Europe just starting construction or being financed. Worldwide battery demand forecasts vary from 6.5 TWh to more than 9.0 TWh for 2030. Research body Benchmark Minerals estimates there is currently a production capacity of 1 TWh. Battery demand in Europe is forecast at 550 GWh in 2025 and 1 TWh by 2030, he said. This is based on the EBA’s own analysis and on motor manufacturers’ announcements (with 15% added for other sectors).

The gap between supply and demand – especially upstream – is very wide, said Sekkenes, adding meeting it is “a good business opportunity”.

The upstream segment of raw or active materials is also facing enormous demand, as is the market for production equipment. “This is also something which, to the largest extent, we import from elsewhere. Production equipment is also something we need to build up our strength in Europe,” he said, adding that China dominates in terms of production and raw materials.

“We need far more skilled people,” he said. Workers in other industries that face decline can be retrained in battery skills. The recycling industry is fragmented, with many questions unresolved: who owns the batteries, how are they transported, etc?

“We’ve come very far in only five years,” he said, referring to a European battery industry that was almost non-existent five years ago. “The on-scale manufacturing picture is very different now and growing but has some issues…we need to focus more effort.”

Feasible battery regulation

Michael Lippert, president of BEPA and Batteries Europe, and director of innovation and solutions for energy at French battery maker SAFT, said he wanted the battery regulation in Europe to be feasible and take the industry in the right direction. Education and skills building are also important, he said. More academic positions and programmes are required, as is educating the general public about the shift in direction to battery energy.

Digital developments and advanced battery management systems – for example as part of the Battery Interface Genome – Materials Acceleration Platform (Big-Map) project is part of a radical shift in battery innovation. It is a consortium that aims for a dramatic speed-up in battery discovery and innovation time; reaching a 5-10 fold increase relative to the current rate of discovery by 2025-30.

Manufacturing improvements are important, he said. Areas include further development of lithium and solid-state batteries, as well as making batteries safer and cheaper, and with better battery management systems. The manufacture of stationary ESSs that are less dependent on critical raw materials is being supported.

R&I in Europe is in the hands of several bodies, each with its own area of activity. “The important point here is that we work together to avoid duplication. There are six working groups for the entire value chain. In conclusion, we believe R&I is a very important part contributing to the European battery industry.”

Lippert is also vice president of the European Association for Storage of Energy (EASE).

Future-proofing the value chain

Ilka von Dalwigk, EBA Policy Manager, said making the value chain future-proof was “not just a technological question”. She told the session: “It’s about collaboration, not only in European industry and academia. Our competitors aren’t resting, they are developing all the time. We should do this as well.”

Roberto Scipioni, technical leader of Batteries Europe, an EU body for researchers and innovators, told the session that digitalisation was “a challenge, but also an opportunity”. He said: “What is it: It’s important first of all because you have to identify each part of the value chain. Digitalisation is an important tool. It’s very important to understand what it is.” It allows visual representation of processes, for example.

In terms of gathering knowledge, he said large amounts of data are required. “We can collect data in many different ways, and we need to homogenise. In Big-Map, we’ve done a lot on the homogenisation of data. The other problem is not only making data available but how we get the data…We need to have a more trust-based market (between researchers and industry, ed.).”

Kristina Edström, Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at Sweden’s Uppsala University, said she felt hopeful about the greater coordination happening across Europe. She is involved in the Battery2030+ research initiative aimed at creating tools for transforming the way people develop and design batteries in Europe.

There is greater work between researchers and industry as partners,” she said. “It’s not industry looking at research, or research sceptical of industry, but a real partnership. We have industry involved in long-term problems.

“We are skilling the students and teachers in schools…All this we need to bring together and harmonise in a European landscape. I think that’s a very good starting point.” Her young students are the research leaders of the future. Stimulating them and providing networks helps them develop, she said.