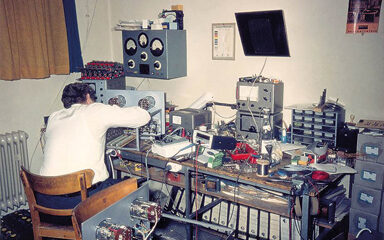

In honour of a triple anniversary year for Digatron, Ruth Williams visited Aachen to report on the company's history and secrets for success.

2013 is a year of celebrations for Digatron Firing Circuits. It is 45-years since Digatron was started in Aachen, Germany, 25-years since the acquisition of Firing Circuits in the USA and 20-years since the opening of Digatron China in Qingdao. Not to mention Rolf Beckers' 65th birthday.

As BEST readers know, Digatron designs and manufactures automated battery testing equipment and formation equipment for lead-acid and lithium‑ion cells . . .

to continue reading this article...

Sign up to any Premium subscription to continue reading

To read this article, and get access to all the Premium content on bestmag.co.uk, sign up for a Premium subscription.

view subscription optionsAlready Subscribed? Log In