No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it. – Albert Einstein

Reconciling management and staff is often a source of frustration. Experience shows that it stems mostly from the differing perspectives of buyer and seller. Those employing are buying and those employed are selling. Each wants maximum return on their investment or payment respectively.

This underlies all negotiations and contracts despite each party recognising the need to be working in a viable and profitable company. Without mutual trust, reaching a way forward that we all buy into, can be a very uphill battle.

Most of us are all too painfully aware that the concept of fairness is usually relative to which side of the fence you dwell on, as this tale, dating back to the nineties, plainly demonstrates.

A return to profit

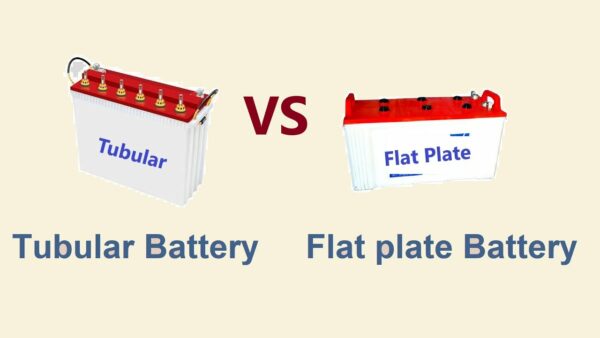

This is a lead-acid battery manufacturer struggling to stay afloat after surviving the great recession of 1990. As part of a multinational, it manufactured 2V tubular and flat-plate cells plus deep-cycle monoblocs for industrial and leisure use, mostly the UPS, standby power, marine and caravan markets. For three years it had suffered from declining profits and was now down to break-even in the first quarter of the year.

The report showed that, in the absence of higher sales levels, costs had to be cut by 5% in order to put the company back into pre-recession profit levels. The question was, how can this be achieved? James addressed the management meeting after the report, and asked for suggestions from each of the managers in turn. The replies were as follows:

Production manager Ed— increase sales or cut the salesforce to suit the lower turnover.

Engineering manager Brian— Automate the assembly process and invest in the latest equipment.

Accountant Rahul— cut both direct and indirect staff and reduce material costs.

Sales manager Stuart— sell the product more cheaply to increase the turnover.

Technical manager Mike— new curing ovens to halve the process time and do online quality tests.

Trade union rep Brendon— take 20% off manager’s pay, drop company cars, increase production bonus.

The meeting ended with a decision to implement a series of measures. These were basically to invest in key, heavily-manned, low productivity areas, namely:

- Install automatic racking equipment at the end of the pasting flash dryer.

- Purchase new automatic curing chambers to cut curing time from 48 to 36 or 24 hours, depending on the plate type.

- Install rotary-type 2-position assembly jigs with one person loading for two assembly jigs. This would replace the process of the assembly burner loading the static jigs and effectively double the output, enabling the removal of some direct production staff.

- Install an automatic pillar burning station for monobloc batteries, again saving direct labour.

- Improve the formation water-cooling baths to reduce the process time from 48 to 36 hours.

Purchasing was put on the job and came back after a week with a total of 1.5% overall cost savings. The savings tally was now up to 4%. James was adamant that 5% was the minimum and a further meeting came to the inescapable conclusion that more workers had to go— it is always the easiest target. Another 10% of the jobs needed to be axed. Obviously, this led to serious conflict, particularly with one union representative, Jason. During an update meeting, he argued that the present situation was largely the result of management error, and yet there were no measures to reduce the overhead costs of senior personnel. James took the trouble to point to a work-study done months earlier had identified the savings to be made by cutting the non-direct jobs in stores, maintenance, and production scheduling. After further discussions with all managers, some junior admin positions in finance, HR and purchasing were also on the list.

The same old story

Despite this, two more people had to go, and after much argument, James decided it would be from the direct labour pool. The production manager Ed was given the task of making the operator cuts. Ed decided that this should be from the 2-volt cell assembly line, in particular where the lid is placed on the box and the grommets are put into the cells. Or it could be from the monobloc assembly line where the battery posts are aligned in the lid before the terminal welding process. This was badly received by Jason who, in conjunction with the assembly line supervisors, said it could not be done. Again, they pressed the need to consider a better bonus scheme to incentivise the operators. Jason also pointed out that there was a lot of resentment from the shop floor as they believed that the company was getting more out of them for less money. This was seen as unfair and a further example of exploitation.

James was now becoming angry: his neck was on the line and time was rapidly running out. He argued that they could not make savings if the workers were paid more per unit— it defeats the objective of cost savings. And wasn’t the security of a job more important than a flawed principle of justice? Jason was, however, very calm and pointed out that a 10% cut in the top managers’ pay plus removing company cars would save a lot more. Why wasn’t that also on the table? He then delivered the message from the line supervisors who argued that this last measure would create bad quality, damage equipment and would therefore be counterproductive. And what about those people who would lose their jobs in a time of high unemployment? Was that not a consideration in deciding the best way forward?

Careless words

It was then that the managing director made a very careless and insensitive comment: “It is what it is.” Then turning to the production manager Ed, he ordered him to work on the assembly line to demonstrate that having one man less could still work effectively.

Subsequently, the line was held up for two days whilst the health and safety department investigated the cause of the accident. Unfortunately, nothing else seemed to go as planned. The savings were not made and some quality issues resulting from poor lid and pillar alignment gave a damaging spike in warranty returns after only two months. To make matters worse, Ed, who was close to retirement, sued the company for negligence due to being put on the job without adequate training.

Despite his frenetic attempts to salvage the company’s fortunes, after 1 month, James had a visit from senior directors at head office. The meeting was, of course, a formality and after just 30 minutes the head office directors had left and James was packing his personal belongings. Although the outcome of the meeting had spread around the factory within minutes of the director’s departure, no one turned up at his door. Nor did they seek him out to give their best wishes or even condolences. Now with his case full and his coat over his arm, he marched tight-lipped through the reception area towards the car park. By chance (probably) he met Jason walking through the door to bring his shift report to the production department. They both stopped to look at each other. It was James who spoke first.

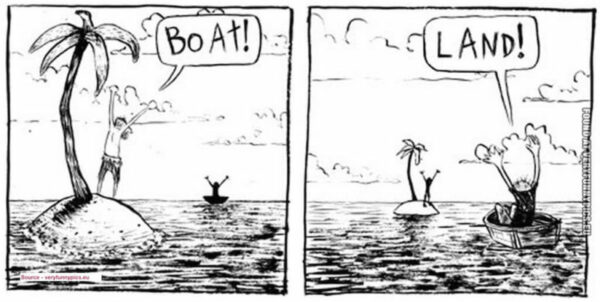

“Well Jason, I guess you won’t have to worry about me anymore, will you?”

There was no reply, but James persisted. “You may also be pleased to know that I have a huge mortgage, a wife and two children plus my mother to support. There is little-to-no-chance of finding another job that will even keep me afloat.”

Jason walked past him and put his report in the production tray. Then slowly turning to look directly into James’ eyes, delivered his parting message: “It is what it is.”