It’s a time of change for the battery recycling industry, which has to adapt to new requirements at a technical and economic level. These challenges and more were on the minds of delegates attending the 23rd International Congress for Battery Recycling (ICBR) in Berlin in September 2018.

The chairman of the ICBR’s steering committee, Dr Jean-Pol Wiaux, told delegates the industry had “entered an area of ‘disruption’— where progress in technology is taking place at record speeds and driving new societal attitudes”. BEST’s Gerry Woolf gives his take on the proceedings…

A promise of a market worth €250 billion and 4-5 million jobs in advanced batteries by 2025 came from Dr Christian Müller of InnoEnergy at the ICBR. But what was missing was the how and where the starter capital would come from to create this ‘miracle’.

These vital facts surrounding the European Battery Alliance were absent as Müller (right) pressed on with something of a Euro battery fantasy. The alliance, kicked off some six months ago, now has 120 stakeholders from the metals industry to vehicle makers. But quite what is being delivered was somewhat bleached out to mere scribes by the sheer ‘wow’ of Müller’s PowerPoint presentation.

Müller relied heavily on ongoing private investment announcements, including Umicore’s €660 million announcement in June 2018— to build a cathode materials plant in Nysa, Poland. This will deliver 400 jobs by late 2020. Then there is the ‘process competence centre’ in Olen, Belgium, with 20 new jobs and set to start in 2019.

French battery maker Saft has also made announcements in collaboration with Siemens and Solvay for solid-state batteries— and these too were drawn into Müller’s numbers. What the other 117 ‘actors” are contributing to the programme wasn’t mentioned. With the image of the European Commission’s energy supremo, Maros Sefcovic, shining out from the screen, this will be one to watch and to measure.

Creation of EU battery industry ‘needs pragmatism’

The lobby group that represents Europe’s non-ferrous metals industry has said there is a need for pragmatism in creating a low-carbon European future with batteries at the centre.

Eurometaux’ public affairs manager Chris Herron told ICBR, in a carefully-worded swipe at the European Chemicals Agency (ECA), a three-part solution was needed to create a new European battery industry— a circular economy, a battery action plan and a non-toxic environment. This was of course a loaded phrase, because Herron recognised that in order to make batteries, hazardous metals are inevitably involved.

Lead, cadmium, cobalt, nickel, manganese and antimony are all considered “hazardous”, but taking a substitution, or worse a ‘ban stance’, would inevitably kill the dream.

Currently, lead compounds and cobalt salts essential for present generation lithium-ion battery manufacture, are in the ECA’s sight for restrictions or, potentially, bans.

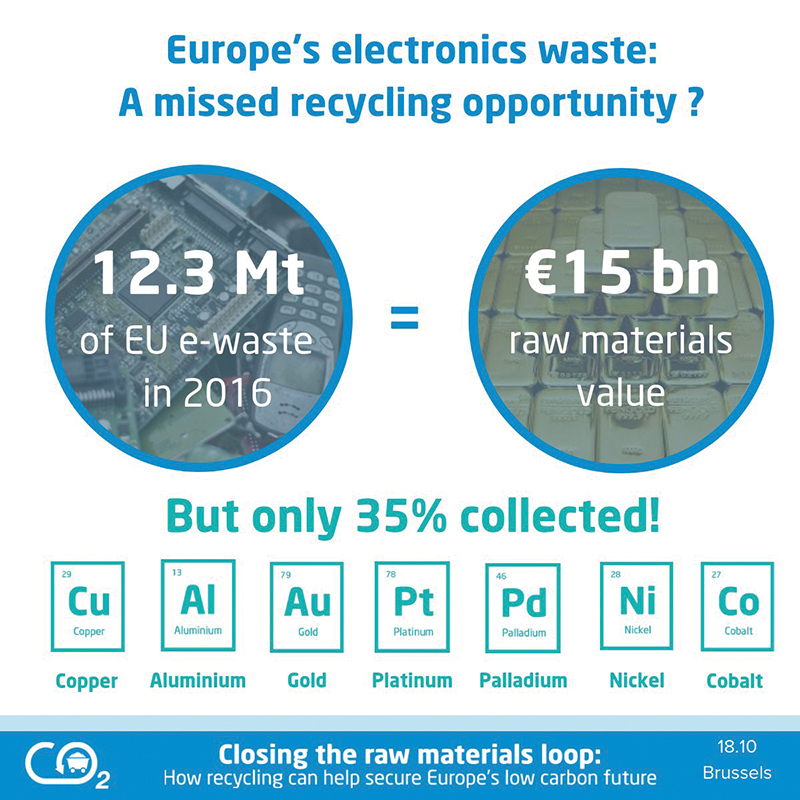

And Herron warned that the circular economy opportunities were already being missed.

In 2017, just 10% of mobile phones from 1.5 billion allegedly disposed of were recycled. That total sum could have yielded 15,000 tonnes of cobalt, which would have been sufficient to provide the content for 1.5 million EV batteries.

Herron recommended a rapid expansion of complex metal waste collection and ensuring that waste went to the right recyclers and to avoid sending material to developing countries.

Getting these factors right was essential if Europe were to have a competitive battery sector— more than 900 establishments and 0.5 million jobs were dependent on it.

Recycling rates must be at heart of new directive

The revision of the EU Batteries Directive and the development of global lithium-ion recycling programmes are imperative in the next 10 years if the world has any hope of stabilising global temperature by the end of the century (as outlined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change).

That was the warning to ICBR by Dr Matthias Buchert, head of the Oeko-Institut’s resources and transport division.

The Directive is not likely to be in place until 2020 at the earliest, but the need for lithium-ion battery recycling is more or less needed immediately according to Buchert’s data, derived from a study carried out on behalf of Agora Verkehrswende— a Berlin-based think tank that aims to promote the switch to a climate-friendly and sustainable transport system in Germany.

The study, entitled Ensuring a sustainable supply of raw materials for electric vehicles, assumes a decline in ICE engine vehicles sales from about 2030 and a gradual uptake of EV.

By 2050, Buchert suggested that lithium demand would have outstripped reserves by some 300,000 tonnes (t) making recycling imperative. To date the main barrier toward recycling is price, with costs of recovered lithium carbonate having doubled to US$12/kg in a year.

It’s the other materials such as cobalt and copper that are more valuable than lithium itself, which could be recovered, but even then maybe less than 5% of the material used in small lithium-ion batteries has been recovered in this way. And this despite efforts by companies such as Umicore, which has a pyro-metallurgical plant in Hobokenin, Belgium with an annual capacity of 7000t of battery material. The intermediate product is a Cu/Ni/Co-rich alloy that is processed in Olen, Belgium. The products are copper as well as high- purity cobalt and nickel salts at battery quality.

The current Batteries Directive wasn’t drafted with any of this in mind said Buchert. Neither does it address lithium-ion batteries or electric mobility. There are no ambitious collection and recycling targets for the electric mobility batteries, nor are there ambitious recovery rates for key materials such as lithium and cobalt.