The lithium-ion battery recycling market remains dominated by China, where economies of scale mean it is already profitable. However, Europe’s lithium-ion battery recycling industry could be cost effective within four years, as cost of recycling NMC cathodes falls. BEST speaks to Nomura Research Institute America* (NRI) about the reasons for this.

While the world was suffering the effects of a universal pandemic, the paradox was that last year was great for electric vehicle (EV) and plug-in hybrid (PHV) sales. These reached 3.2 million across the globe— almost one million more than 2019, according to electric vehicle database EVvolumes.com. For Europe the news was even greater, as the European Union’s stringent CO2 regulations drove total sales in Europe to finally overtake China with a 137% growth and a market share of 20%.

It’s clear that a huge EV market is forming in Europe and China, where the respective governments are using major incentives and regulations to promote the industry. In Japan and the US, the EV market is expanding at a slower rate— partly due to governments not being as focused on growing their respective markets.

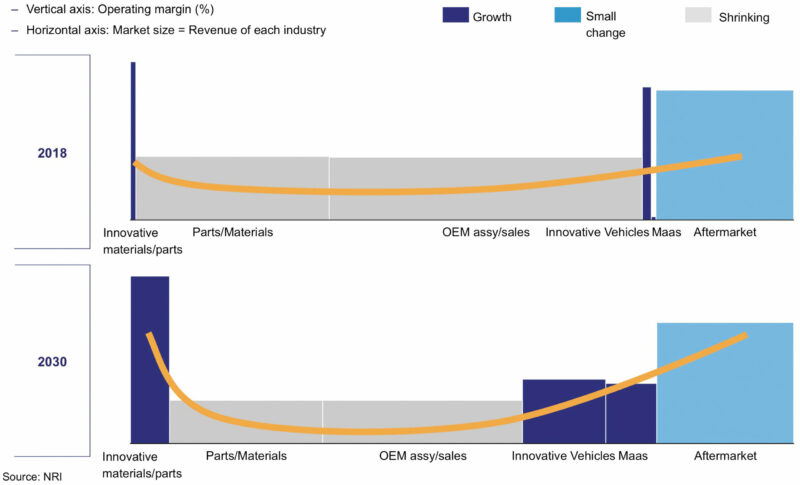

As growth continues, the profit pool in the automotive industry is expected to change dramatically as the expansion of EV adoption makes it easier for anyone to build a vehicle, and at the same time add value to materials and charging services (Fig 1). Given this acceleration of the smile curve, it can be assumed that lithium-ion battery (LIB) recycling, which is both downstream and upstream of EVs, will become an even more important theme in the future.

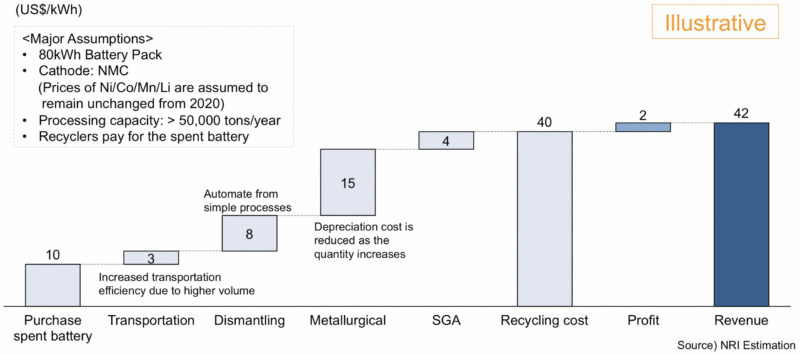

In Europe, the lithium-ion battery recycling industry could be profitable within four years, as the cost of recycling NMC cathodes is set to fall $23/kWh to $40/kWh. The decline of overall cost will come from lower dismantling and metallurgical-recycling costs.

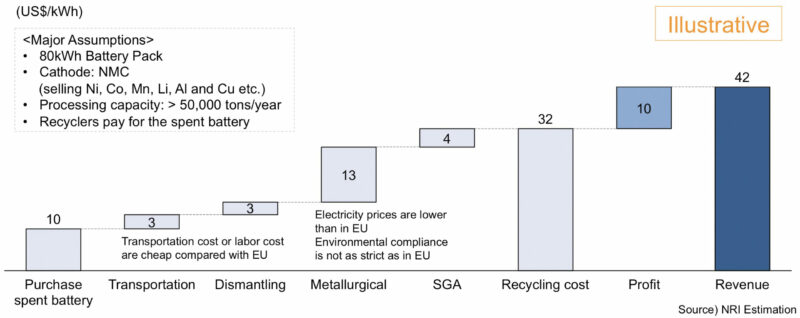

In comparison, China’s cost of recycling last year was around $32/kWh, with recyclers earning a £10/kWh profit— even if they paid for the used battery.

Creating a market

With the EV/PHV markets expected to continue to grow at a CAGR of more than 20% in each sub-segment, establishing recycling networks for LIBs will be an equally important factor in realising a sustainable electric vehicle market in the future.

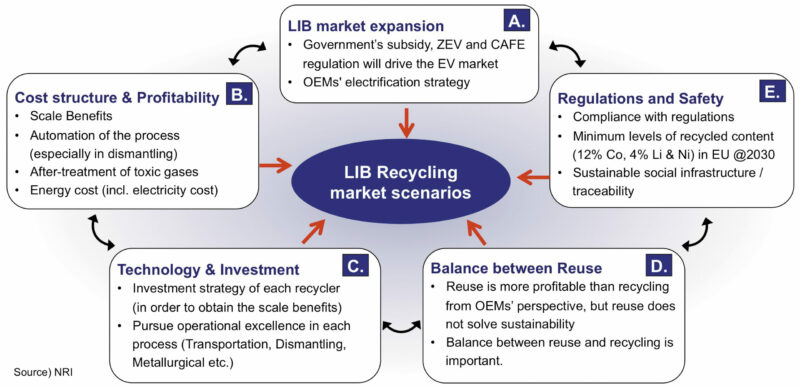

However, there will be key drivers and restraints acting on the business; multiple factors need to be discussed in order to capture the market outlook for LIB recycling (Fig 2).

Nomura research Institute (NRI) considers the following five factors to be important:

- LIB market expansion,

- Profitability,

- Technology & Investment,

- Balance between Reuse and Recycling,

- Regulations and Safety.

These factors vary from region to region, and therefore it is necessary to consider different scenarios for the expansion of LIB recycling in those regions.

NRI believes a number of factors will have to be realised if the market is to ensure suitable LIB market expansion. The first will be the influence of EV/PHV sales, especially with government support and OEM strategy, on the future LIB recycling market.

Today’s LIB recycling market is concentrated in Asian Consumer Electronics; China and Korea have a dominant share (around 90%) of the market, partly because many lithium-ion batteries are imported from the US or Europe. Since the volume of waste batteries for EVs is small, the focus is on processing batteries from consumer electronics such as laptop PCs or mobile phones.

Research indicates that more than 20 companies are involved in the recycling of waste batteries in China, along with at least six companies in South Korea. By contrast, the processed volumes of lithium-ion batteries are still low in EU and North America; the main reason for this is that batteries in those regions are not primarily collected through ordinary collection schemes but are exported, contained in equipment, or sold for reuse to Asian processors.

Therefore in the coming years, Japan, Europe and the US will experience the birth pains of starting up their own LIB recycling industries. On the other hand, China will not need to do so because they already have an established recycling industry that has been cultivated for consumer mobile batteries.

Cost Structure & Profitability

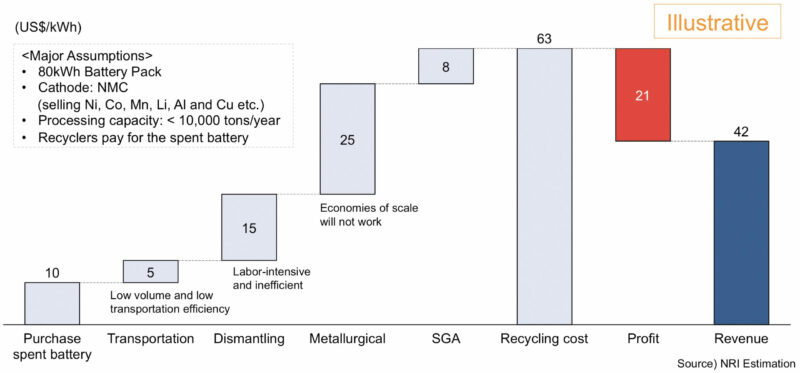

NRI believes that profitability is one of the biggest hurdles to the LIB recycling business. The industry cost structure is highly dependent on region-specific circumstances such as regulations, battery demand, and infrastructure. For this reason, NRI compared the simulated case studies between Europe and China in order to show the regional differences quantitatively.

NRI estimates that it is difficult to make lithium-ion battery recycling economically viable in Europe (or the US) due to various preconditions that function as headwinds under current conditions. The graph (Fig 3) shows the selling price and processing cost for 1kWh of lithium-ion batteries, which has been calculated based on certain assumptions regarding the situation in Europe.

Based on the resource price in 2020, it is estimated that the sale of cobalt, nickel manganese, lithium, etcetera, which is extracted from NMC batteries, is about $42. In terms of profitability, the total cost of recycling that battery would be much higher than the selling price.

There are multiple reasons for the high cost. The first factor is the lack of economies-of-scale in the transportation, dismantling and metallurgical process as well as in selling, general and administrative (SGA).

The second factor is the high-required investment in environmental equipment, such as fluorine gas treatment. The next is that the dismantling process cannot be automated, resulting in high labour costs. The final factor is the assumption that recyclers will pay to buy waste batteries.

In some cases, recyclers are paid along with the supply of waste batteries, but NRI believes that in order to establish a sustainable business model, waste batteries should be regarded as valuable.

However, NRI believes that after 2025, Europe should be a profitable market for lithium-ion battery recyclers due to increasing economies-of-scale (Fig 4). The company estimates that as the volume of waste batteries increases, so will the efficiency of transportation, and there will be room for automation in dismantling. This scenario will play out even if the price of nickel, lithium and manganese remains the same.

NRI, therefore, estimates the business environment will be profitable within four years because of cost reductions, and hopes that by 2030 costs will be even lower than 2025, and the industry will be even more profitable.

On the other hand, China’s battery recycling business is already profitable, even if the recyclers pay for waste batteries due to its scale advantages (Fig 5).

In the past— before 2017— there were not many recyclers in China, so recyclers were paid to receive waste batteries. However, as the number of recyclers increased, and the competitive environment intensified, batteries were offered for free around 2017-2019. In recent years it has become common for recyclers to pay for waste batteries in China.

Even if the same assumptions are used for Europe, the scale of recycling plants in China are already so large that it has become a profitable business environment; the country’s cost structure is also positively affected by factors such as lower electricity costs and less stringent fluorine gas treatment regulations than in Europe.

Technology and Investment

So how can Europe and the US’ LIB recycling business compete? As typical challenges/barriers in the recycling business, scale is the first barrier to overcome. In addition to this, the hurdles of recovery systems and technological development must also be cleared.

However, it is not easy for a single recycler to overcome all of these hurdles on its own, so it will be important for multiple companies to work together.

So how do recyclers build their scale? It requires major capital investment; this means the extent to which recyclers are able to raise funds will be a KFS (Key Factors for Success) for them. Reaching suitable economies-of-scale will also depend on the sector developing technology that can help achieve higher recovery rates of valuable elements— ie materials.

Today, a key factor in scaling-up recycling operations lies in the balance between reuse and recycling.

There are major differences between regions, with regard to the balance act: for example, in Japan there is a lot of discussion about reuse, and recycling does not seem to be a major area of focus. On the other hand, in China, due to the large number of consumer LIBs, recycling has attracted more attention than lithium-ion battery reuse.

Actually, until recently, five recycling companies were on the whitelist (the list of recommended suppliers from the China government), and all reuse companies were excluded from it. However, research indicates that more than 20 reuse companies were registered in the whitelist last year. This indicates that China appears to be paying more attention to reuse.

Meanwhile, in Japan, several players are developing LIB recycling technology, but not as actively as in Europe and the US. Unlike the situation in Europe and North America, where several promising startups specialising in lithium-ion battery recycling have been established, in Japan, large-cap companies (with a market capitalisation of $10 billion+) are engaged in this business as part of their new business model.

NRI believes, to achieve total optimisation, it is important to appropriately combine reuse and recycling, rather than focusing entirely on reuse or entirely on recycling.

Although regulations in China have gradually become stricter in recent years, there are still illegal players, and the existence of such players will be a challenge for building a sustainable battery recycling industry— not just in China but in many other developing countries.

In China, five companies are leading players in the country’s LIB recycling industry in terms of scale and technology. Despite those companies being registered on the whitelist they still find it difficult to receive all the spent batteries because of the irregularities in the market.

On the other hand, an issue in China’s lithium-ion battery recycling industry is that small and mid-sized recyclers are operating without complying with regulations— posing a challenge to compliant firms. Of course, the Chinese government is aware of these illegal recyclers and is trying to crack down on this practice. Despite regulations being tightened in 2019, the situation has yet to fully improve.

Future scenarios of LIB recycling

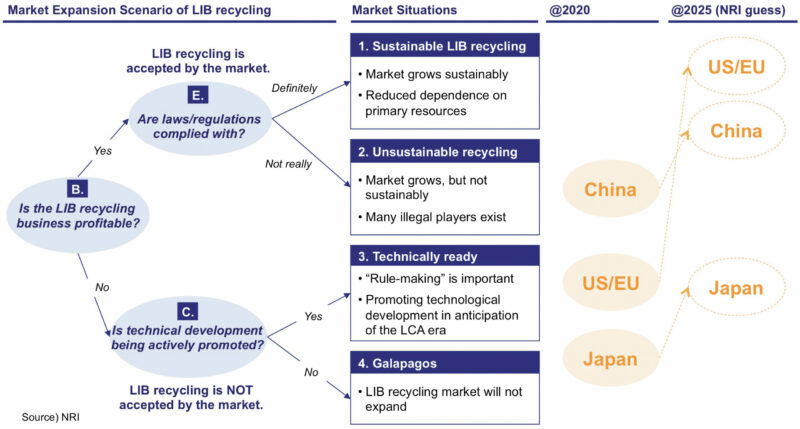

NRI has developed a scenario for the LIB recycling market according to the factors mentioned above, and it believes cost structure and profitability, regulations and safety, and technology and investment are especially important (Fig 6).

The ideal state to aim for is sustainable LIB recycling, where the recycling is economically viable and all players comply with regulations, but NRI does not consider any region to have reached that state as of 2020.

Unfortunately, China will not be a truly a sustainable LIB recycling industry this year because of the existence of illegal mid-small players, but NRI hopes this situation will change by 2025.

In Europe and North America, although LIB recycling is still not economically viable, technological development is very active, including startups and other emerging players— which is a very good thing for the industry.

Some Japanese companies are piloting LIB recycling, but, unfortunately, NRI believes that few major companies are serious about it because it is not economically viable— for now. If this continues, there is a concern that Japanese companies will fall behind after 2025, when the market for LIB recycling is established.

In order to launch a LIB recycling business, it is necessary to cover a wide range of capabilities in a well-balanced manner, from technology development, collection, process treatment, off-taker acquisition, and rule-making.

Since different regions have different progress scenarios, business plans need to be developed for each region.

For LIB recyclers, a major point of strategic consideration is how to build a regional strategy.

*This article was co-authored by: Akihito Fujita (senior manager at NRI), Satoshi Ikehata, (principal, NRI), Hisashi Yoshitake (senior consultant, NRI), and Jeremy Fuller (senior consultant, NRI-America).