Swedish start-up Cling Systems is aiming to run the world’s biggest database for used battery lovers on a dating-like online marketplace that matches buyers and sellers. Andrew Draper found out more.

He said the market in EV battery recycling and reuse is still emerging: “Over time, quite quickly, we realised that recycling is still very nascent. The way of actually logistically handling waste batteries. The recycling is very, very tricky from a safety standpoint, but also from a regulatory standpoint. And all the paperwork that is required… that gives you the right to ship hazardous waste over country borders.” The company then looked into the second-life market and found many companies are starting and building stationary storage on used EV batteries.

With that link between second life and recycling, they “kind of enable each other,” he said. “That second life is pulling out the good batteries that can be reused and leaves only the bad batteries.” But sellers do not always have a clear idea of batteries’ worth and this freezes the market activity, he said.

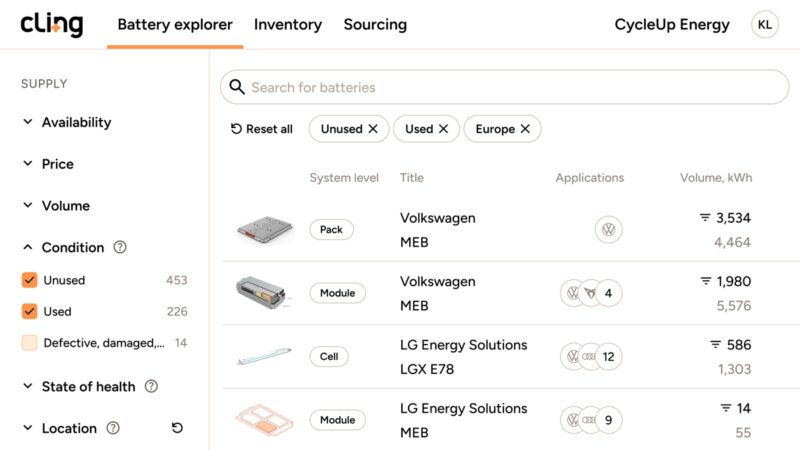

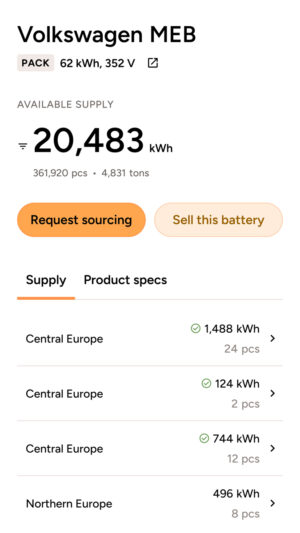

Cling’s role is to act as a broker, facilitating deals on its electronic platform for either second-life usage or recycling. Buyers want a reliable supply, which is not always available. “And so we work with the buyers to sign offtake agreements or supply agreements that gives us the ability to go out and source batteries on the supply side. And then we collect them. We warehouse them, we can test them through partners if necessary. And then we deliver the volume to the demand sider.”

Last year, Cling handled some 20MWh of used batteries and is aiming at 100MWh this year. It deals with cells, modules and packs. The Stockholm-based business, just four years old, works with partners for logistics and warehousing. It counts almost 500 traders in its network covering 36 countries.

The data it holds in its database covers information like cell configuration, size of modules, capacity and voltage C rate. “And to the best of our knowledge, we have the biggest and most comprehensive database on batteries out there,” Bergh said.

Safety

Asked how Cling ensures safe operations, including at warehouses it does not own, Bergh said the company chooses facilities that are compliant in handling batteries. Rules vary widely and sometimes are minimal, so it works on a case-by-case basis to check certification. This includes plant visits.

“So despite the common kind of view or idea of what a car dismantler is, that is kind of a scrappy and so on, it’s starting to be really good. They really care because they get the batteries regardless. And so it’s very much in their interest to have safe warehousing,” he added.

The warehouses have specially trained staff and use thermal cameras to monitor battery activity, both during and after vehicle dismantling. There are also specialised containers. But if a battery comes in from a crashed car, no-one knows the battery’s state of charge, he admits.

This early market has no standards for checking or requirements for testing the state of charge. That is up to the parties involved, he said, and that poses a challenge. What he typically sees are agreements between recyclers, car dismantlers and insurance companies. Insurers are very early in their approach to the market, he said.

He added that his company is not developing hardware or testing software. “What we’re trying to do is to bring everyone to the same table and that just enables the market and ecosystem to make the best decisions.”

Cling wants to work with more battery manufacturer OEMs to secure its supply. The waste batteries are often a result of over-production of modules, for example, as well as coming from crashed vehicles. Sometimes auto manufacturers have bought too many batteries and want to sell them.

Bergh said there is a polarised view, from OEMs who say second life has no future due to recycling quotas to those who argue repurposing is more sustainable.