The dominant chemistry for battery recycling is set to remain lead until the mid-2030s, according to market analysts. While lithium batteries (and the EVs they power) are on the march, lead battery recycling will continue as king for now, they say. Andrew Draper reports.

Patrick Curran, senior partner and analyst at Archimedes Industrial Advisory & Investments, echoed the view of many that there has been a dramatic overbuilding of capacity for recycling: “You see a trend and everyone’s jumping on it and they think it’s going to be a gigantic business. Maybe it will be, maybe it won’t be. I never believed the hype, and the only reason I didn’t believe the hype is because batteries take a long time to come back from the field.”

Curran said the average lead battery lifetime is 3–5 years, and longer for lithium as it might go for second-life repurposing. “So they are building capacity for a product that’s not going to come back yet because the market is not at equilibrium like it is with lead-acid.

Market equilibrium

With reference to lead-acid, he said: “The amount that gets shipped out is roughly equal to the amount that comes back for recycling. But the lithium hasn’t matured to that point yet…The amount of batteries going out into the field versus the amount that is coming back is dramatically different.”

He believes equilibrium will be reached in five years’ time. “I would say there’s probably at least quadruple the amount of capacity out there than the supply. And you can see this in the aftermarket pricing for spent lithium batteries. The demand is driving the price up because it’s musical chairs.

“They’re trying to go after a very limited amount of batteries for gigantic availability of capacity. And some of these companies are start-ups, so if they don’t have lithium-ion batteries to feed the plant, they’re going to die, and they are dying, like Li-Cycle.”

The effect of this is larger players sit back and watch, then enter the market and scoop up available batteries and recycle them themselves, he said.

Black mass feedstock

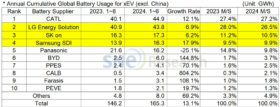

Analysis body Rho Motion held a webinar on EV battery recycling in May. Referring to its latest Battery Recycling Quarterly Outlook, Mina Ha, who leads on recycling research at Rho, said black mass feedstock, including from end-of-life EV batteries and ESS will remain in under-supply, but this will change as the market develops.

The growth in feedstock this year will be about 40% in North America, over 60% in Europe and total 30–40,000 tonnes. In China, Rho is expecting a 49% increase in feedstock and to take most of the capacity. Its forecast has been adjusted down from an 80+% growth forecast for this year as the market has slowed.

Rho believes the NCM market will continue to dominate for some time, though LFP recycling is emerging.

Worried about chemistry

According to Curran, lead-acid is not going away and is still going to be bigger than lithium almost 10 years from now. But the changing chemistry of batteries being produced is altering the economics of recycling, and he is worried.

“The thing that terrifies me about the economics of this is the changing chemistry of the batteries getting produced. And there’s been a big development in sodium batteries. It’s a Norwegian company and they’re partnering with a Chinese company to make salt-based batteries. It doesn’t get much cheaper than that. So that changes the economics of recycling dramatically,” he said.

It might mean batteries become so cheap they could become disposable, although battery passport schemes may force auto manufacturers to deal with the recycling at end of life.

Market forecasts

A report from data company Transparency Market Research (September 2022) forecast the global lead-acid battery scrap market will reach a value of $28.8 billion by 2031, with a CAGR of 10.5% between 2022 and 2031. The lead batteries used in industrial and automotive applications, including uninterruptible power supplies and solar power storage, is expected to result in a rise in the lead battery scrap market during its forecast period, it said.

A growing awareness of the value of recycling, and not dumping batteries in landfill, is resulting in a surge of recycling initiatives, it said, and this will drive the scrap battery market upwards.

The lithium-ion battery recycling market is set to hit a value of $6.6 billion by 2028, according to a report by Fortune Business Insights (October 2022). It will see an 18.5% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) from 2021, it said. The construction of new recycling facilities involves high investments, which, in turn, may hamper the demand for lithium-ion battery recycling, it added.

Killing informal recycling in India

Tough new waste management rules in India will eventually choke off informal battery recycling, according to the head of India Lead Zinc Development Association (ILZDA).

L Pugazhenthy, known as Pug, told BEST the battery waste management rules implemented some 18 months ago are working. Extended producer responsibility (EPR) is now taking effect, he said.

“So that is a new experiment for India,” he said. “You have to wait and see how this going to work.” He said 1.5 million tonnes of lead is produced every year in India. Of that, 1.2 million is secondary lead.

EPR places responsibility on manufacturers to ensure safe collection, safe storage, safe transport, safe recycling, and occupational healthcare precautions in lead smelting or lead recycling. “So the manufacturer is more accountable and more responsible for all these activities,” he said.

Pug said the scheme works a bit like Europe’s battery passport idea, though is not as detailed. He thinks this may come later.

Companies have to submit annual returns, annual reports are monitored by the authorities, and changes are enforced. He said EPR provision may arrive in other Asian countries too, also copying the European model.

“And that’s a good sign,” he said. “Rather than imposing regulations, you make the producer responsible, accountable and fix the responsibility on him. And if he fails, there will be a penalty.” Informal recycling has receded in the face of this new regulatory regime, he said, but he believes it still accounts for some 20% or so of all recycling.

“But more or less everybody now – all the regulatory bodies in various provinces and states of India – they’re insisting on this formal green recycling and safe recycling. So more or less that supply chain for the informal sector has been choked. The producer collects, gives it to authorised recyclers, buys lead from them for new batteries. So it’s a kind of circular economy there. And that’s a good sign.”

He added the government of prime minister Shri Narendra Modi is very focused on wiping out the informal sector everywhere.

Largely mechanised

Pug said Indian battery recyclers have largely mechanised and gone for rotary furnaces for melting the lead and refining kettles for making the lead. “And one good thing is we have given up more or less that manual battery breaking, which was there for a long time.” The pollution control board, ministry of environment and others are all insisting on mechanised battery breaking, he added.

The market has consolidated with 3–4 big players with some 72,000 tonnes per year capacity each, up from 10–15,000 not so long ago. He added: “We used to see tiny tots in lead recycling. But now this is becoming a big-scale activity, big scale of operations. And they’re all technologically very good plants. Anybody from overseas would certainly like to see those plants.”

Not only is the technology good but the companies are also taking good care of occupational health, he said. This will spread to other countries, he thinks. “I hope this will all percolate to Nepal, maybe Bangladesh or Pakistan, or other south-east Asian countries. And I think gradually this will spread.” Indian tech consultants and equipment suppliers are already going to other parts of the world, he noted.