Batteries Event, held in Lyon, France, in October, provided an opportunity to learn about technological trends and how companies are adapting to a challenging market slowdown. Andrew Draper reports.

The conference and exhibition continues to grow, this time attracting nearly 1,200 participants, over 100 exhibitors and 175+ speakers from the battery industry. In 2010, there were 500 attendees, 65 international speakers and 50 booths. Participants said they found it a good size for doing business and finding their way around and would not like to see it get much bigger, a view echoed by the organisers.

The conference included presentations on market issues and trends, battery production in Europe, safety and regulations. There were many specialised sessions, covering topics from anode and cathode materials to thermal management, separators, zinc as an alternative and recruitment.

On building a sustainable battery recycling value chain, Philipp Wenz of Germany’s BASF said the biggest challenge is turning internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles to electromobility. “If we want to get rid of CO2 we need to do that,” he said in his presentation. He presented data from the International Council on Clean Transportation stating that greenhouse gas emissions over the life cycle of a passenger car are up to 70% less from electric vehicles than ICE cars.

He said it was necessary to keep materials coming into its European value chain, as important battery materials are not easily available in the EU, and are mostly sourced from third countries –overwhelmingly China.

Wenz noted the slowdown in EV market growth and delayed gigafactory plans. CAM producers are also reconsidering projects, which he said “creates uncertainty and is not good for investment.”

The company operates in the US, Japan, China and in Schwarzheide, Germany. Here, it makes black mass and refines prototype metal. It runs a fully automated pilot line which can process up to 15,000 tonnes of EV batteries and scrap. It functions “like a boot camp” and is the basis for a large-scale black mass refinery, he said.

The classification of black mass as hazardous waste must be clear and consistently enforced across Europe, he said, adding it also needs to go into the regulations. He called for a ban on “waste tourism”, saying “there could be black holes for easy manipulation of black mass.”

Juha Saaranen, engineering manager at Jot Automation in Finland, argued that greater automation would result in rising recycling rates as well as greater safety levels. “The batteries arriving may be in various conditions,” he said in his talk on automation. “So safety is one of the most important topics to ensure the operators are safe.”

He referred to the chicken and egg problem, where low volumes do not warrant investments (yet), leading to poor large-scale adoption.

He said a major problem identified in the industry is the huge variety in chemistry. Battery passport requirements and QR codes instantly provide details on correct handling of end-of-life batteries. Automation can include “pre-taught recipes” such as data on picking points, deep discharge parameters and handling protocols.

Vision tools identify the condition of modules while machine learning algorithms enhance the ability to handle module conditions, he said.

China dominant

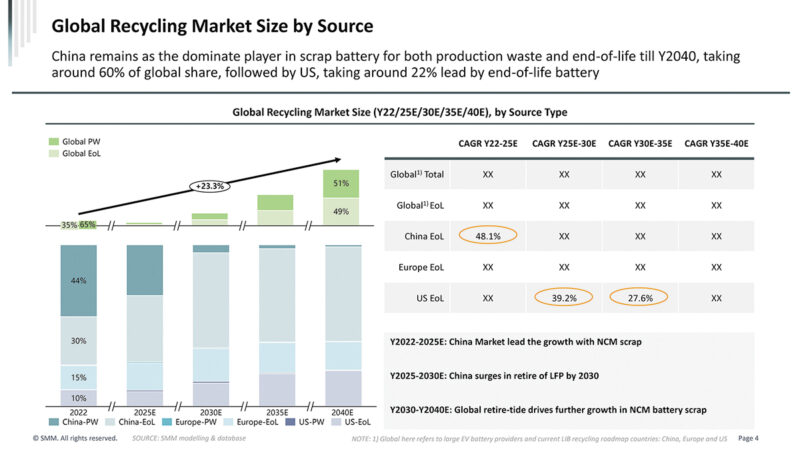

Yettie YI, vice president at Shanghai Metals Market (SMM), said in her presentation on China’s potential in lithium-ion battery recycling that the country will remain dominant in the scrap battery market until 2040. China will take around 60% of the global market for production waste and end-of-life batteries. It will be followed by the US, picking up around 22% (by end-of-life batteries).

The CAGR will be 48.1% in China from 2022–25, she said, while the US is projected to have 39.2% in 2025–30, falling to 27.6% in 2030–35.

She said in the second quarter of 2024, China had almost 70% of the black mass trading market worldwide. Its output was 69,000 tonnes (43% of the world total). The EU held 28% of the global market, while the US was on 15%, she said.

SMM claims 400,000 active daily users of its data and other services.

Many speakers talked about China and its powerful rise. Andreas Bareid, head of e-mobility at QAD and co-chair of NAATBatt’s battery technology onshoring, said in his presentation that China is well ahead of the West in terms of technology.

Vertical integration

It has 120 OEMs, down from 300 in 2019, and released 150 electric vehicle models in 2023. This is based on massive investment and a vertically integrated battery supply chain.

The US is onshoring from Asia-Pacific (APAC) and Europe as a result of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Europe’s Green Deal is not enough to mitigate the onshoring effects of the IRA, he said.

The onshoring of battery technology has meant an upscaling of capacity in the US, for example, and transfer of technology from Asia. “We have a problem, gigafactories are being built on a political basis, not where they have access to universities etc. Demand is now falling, we’re having less adoption of EVs, while China is able to pump out more affordable solutions to consumers,” he said.

He went on to argue in favour of vertical integration: “I don’t see how you can rely on a foreign supply chain and be effective. If you don’t have your own, you’ll never be able to scale up to where you want to be…You need to have a whole programme in place. I’ve not seen many of the players doing that. One thing I see from the more successful ones is they’re bringing in expertise, applying government and investor funds.”

John Kwon, general counsel at China’s CATL, explained in his talk how the company always pursues a vertical integration strategy. He pointed out that despite being ranked as the world’s biggest EV battery maker, it is only 14 years old and used to make batteries for laptops.

The company is supported by a strong research effort backed by an R&D budget of $3 billion a year, representing 6% of its turnover.

He explained how the IRA prevents CATL from establishing production in the US and critical minerals have to be sourced in the US or a compliant country.

“To create the whole new supply chain for that market has created cost pressures. The supply chain we were able to create was vertical integration,” he said.

“We invested in rare metals – in Indonesia, China, etc. and processing of the metals in China. Most is done there. It’s not a national strategy because it’s dirty. It’s very convenient for us and Korea to process, it just happened that way due to economics.”

The Critical Minerals Act in Europe has added cost pressures as it stipulates a minimum level of recycled materials to be used, he said.

“Overall, beyond these pressures, how do we optimise costs? We’ve done it by investment in the mines and lithium, in the processing and to invest in battery part factories that make cathode and anode, and then in cell and module production, packing and recycling.

Building the best battery factory comes down to vertical integration. “If you don’t have control over that how will you control offtake of lithium. It’s through this ecosystem that we’re able to bring to the end-customer the most effective product…overall the main principle is how we manage cost.”

Challenging environment

Sebastian Wolf, COO of PowerCo, outlined the experience of the company set up by the Volkswagen group (600,000) employees in 2022 to make battery cells, not just for VW.

He said: “We are in one of the most difficult of times…I’ve never seen such a challenging environment as now.” The market has gone from skyrocketing demand to slowdown, albeit still growing.

The company is facing pressure for overinvestment in its batteries. There is record growth in technology, which changes on a monthly basis, he said. Costs are overrunning.

“We’re all in the same boat – we need a strong customer base and competitive cost base. We need to have a competitive cost structure and need to understand how we source.

“If you look at equipment suppliers, there aren’t too many in Europe,” he said. His company, part of a giant, has transformed “from being a teacher to becoming a student” to gain a competitive advantage.

The boss of cell maker Automotive Cells Company (ACC) said, in his talk, the company is considering introducing additional chemistry batteries to its range to help it respond to the slowing EV market. At the same time, he called for more public subsidies to support the industry.

Yann Vincent said the company would make a decision next year on whether to introduce new chemistries to allow it to cater for both low cost and high energy density batteries, which are more expensive.

He admitted the company is behind on its ramping up objectives, but said it so far had met all its commitments. Explaining the company’s decision to put on hold the construction of new gigafactories in Italy and Germany, he said: “It’s a very complex industry. Any time the market isn’t subsidised, there is no market. In Germany they cancelled subsidies, and immediately the market went down. The same in Italy and Spain.”

He said all cell manufacturers planning to increase capacity in Europe have reduced forecasts and some had even moved out of Europe.

“Considering the investment needed, and with the market slowing down, we need to be more cautious.”

The next Batteries Event will be in Dunkirk, northern France, from 1–3 April.

Slowdown in EV sales growth represents an opportunity for Comau solutions

The slowdown in the growth of electric vehicle (EV) sales is providing Italian automation company Comau the opportunity to develop new solutions.

Gian Carlo Tronzano, head of the e-mobility global competence centre at Comau, told BEST: “This slow-down is giving us the opportunity to develop what we were not able to develop in the last few years.”

This includes new portfolio solutions. The company was already working with prismatic cells but is now working on developing blade pouch cell solutions, he said. It provides cell formation and testing technologies as well as solutions covering all phases of the battery module and pack production cycle, and end-of-life battery dismantling.

Tronzano sees the EV market slow-down as temporary. “We see some customers already shaping their plans.” They are also fixing mistakes in terms of forward planning, he said.

Tronzano said Comau continues to invest heavily in research and development for the industrialisation of next-generation technologies, including solid-state batteries, hydrogen fuel cells, battery module and pack assembly, and battery trays processing. Batteries make up around 40% of Comau group revenue, he said, having grown rapidly over the last five years. The battery business is growing faster than overall group revenue, he said, aided by business in China.

Tronzano declined to give much away about projects, but said the company is working with OEMs and battery companies on battery manufacturing projects up to 10GWh. It is working with car OEMs in China on large projects.

Tronzano said the company has also recently acquired a large-scale project for cell formation on an industrial scale.

He said the business works on multiple chemistry projects and can readily switch between them according to customer needs. In the EV sector, it works with prismatic and pouch cells, but is seeing a growing ESS sector springing up.

The business is focusing much of its European R&D work on new technologies rather than individual products, he said. And here, the challenge is moving from pilot- to industrial-scale production.

Pillot sees gradual switch to LFP

Christophe Pillot, director of Avicenne and organiser of Batteries Event, believes the electric vehicle market in Europe will increasingly open up to lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries to serve small and medium vehicles, while nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) batteries will continue to be in favour for bigger cars.

In an interview with BEST, he said the EV market is still increasing, also in Europe. “The demand is there, the EV market is not decreasing. Even in Europe, it’s still increasing. Less than before, for sure, but you cannot expect a 50% average growth rate forever, for sure.

“So the growth is less important, but it’s still growing fast. Then of course with EVs the main issue is the price.” That is a real problem for Europe because even if the right batteries are made – such as NMC – OEMs such as Stellantis and Renault are asking for “a low, low, low, low price”.

He said “nobody bet on LFP in Europe”. This is changing now, but it comes late. They can offer batteries at some $120/kWh, but what is needed are batteries at $60/kWh, he said.

He thinks there will be a rebalance and gradual switch rather than a sudden switch. Big cars and those offering long range will need NMC batteries, he said. “I think that medium and low-range cars do not need high NMC batteries with very high range and very big packs. So I think in medium and small cars, they need 40–50kWh batteries with LFP. And the price will decrease with that, for sure.”

EV take-up is being influenced in part by negative media coverage, and Pillot believes it will be bolstered when the next generation of motorists emerges without hang-ups about whether their vehicle will have enough power for the daily commute. It is the same generation that does not feel the need to print out travel tickets, just in case.

In his presentation to the event, Pillot said LFP/LFMP and NMC will be the main battery chemistries in 2030, together having some 85% market share.

Europe has a lack of gigafactory capacity, equipment, labour and recycling capability, he noted. It has an excess of battery scrap, which it exports to South Korea as they know how to recycle it and have the capacity to do so, he said.

China

Pillot believes collaboration with China is the way ahead for Europe rather than trying to reduce its dependency. He refers to recent comments from Robin Zeng, chairman of CATL, who believes gigafactories in Europe are working with the wrong design, wrong equipment and wrong processes.

“I think that one way to be faster, and I think it could be a good way, is not to make war with the Chinese, but to make some collaboration, some partnership between Chinese and European companies.”

The alternative is to fight, he said. “How we can fight – we are more expensive, we have less experience, less knowledge. So, we have to put some tax on, or offer a lot of incentives – and that’s the only solution. And even with that, I think it’ll be difficult.”