The path to a spanking clean, environment-friendly India by 2030 is becoming increasingly paved with lithium-ion as the country embraces the battery technology to ease its reliance on imported crude oil. Dipak Sen Choudhury meditates on missed opportunities in the country’s journey to net zero.

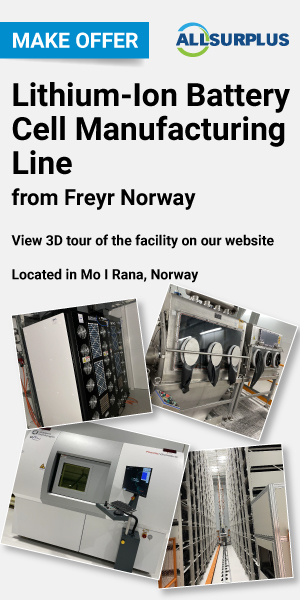

The journey has started; India has set off on its journey to manufacture advanced chemistry cells (ACC) for mobility as well as energy storage applications. Four aspirants, amongst ten entities that submitted bids under the ACC Battery Storage Programme, qualified to receive the generous ‘Production Linked Incentive’ announced by the Government of India for investors who set up units in the country to produce a combined 50GWh of advanced battery chemistry storage systems.

Those aspirants were: Reliance New Energy Solar, Ola Electric Mobility, Hyundai Global Motors Company and Rajesh Exports Limited. All four will receive incentives under India’s programme to boost battery cell production in the country.

For the government, this was vital, as without in-country cell production capability the grand vision presented to the world of a ‘spanking clean, environment-friendly India by 2030’ would fall flat.

The onus is now entirely on the awarded organisations to set up manufacturing units that will start production in two-years time with a minimum 25% indigenous bill of materials (BOM) content that would have to be increased to 60% in five-years time. The numbers are important, as any slippage will result in punitive debits to the eligible government subsidies, which will be disbursed over a period of five years on sale of batteries manufactured in India.

The haste is quite understandable. India’s crude oil import bill for the financial year 2021/22 came to $119 billion, up from $62.2 billion in the previous 2020/21 year. Covid and other factors had kept the oil prices subdued whereas, in the last year, oil prices were on a runaway rise as the global economy got back to some form of normalcy, followed by the totally avoidable Ukraine war.

India imports 85.5% of her annual crude oil requirement and her whole economy has always remained highly vulnerable to global oil price shocks. Reducing dependence on hydrocarbon fuels, particularly in the vehicular segment, can be a major relief to protect the economy from the uncertainties of global political and economic crises.

Emerging options

Going forward, let us look at what options have now emerged. It is important to recall that the government announcement was strictly technology agnostic. The technical requirements to qualify as an ‘Advanced Chemistry Cell’ involved a matrix of energy density and cycle-life. No reason to assume that only lithium chemistries could qualify. Yet at least 40GWh of the awarded capacity is lithium, with the other 10GWh still to be announced. In fact, even outside the four awardees, there has been a press announcement by one of the country’s battery majors that it would invest in a 12GWh greenfield battery manufacturing facility— the chosen technology being lithium only.

And there, perhaps, lies a tale of missed opportunity. The road not taken…

India has no lithium. Not yet. In 2020, it was announced that India had struck lithium in the southern state of Karnataka with an estimated reserve of 14,100 tons. Then, in 2021, the Atomic Minerals Directorate for Exploration and Research (AMD) reportedly found a 1,600 tonne lithium deposit in the province. But that would not be good for even one year of India’s projected production capacity. So where does the lithium come from?

It’s known that 80% of the global lithium supply chain is controlled by China. However, two of the most densely populated countries in Asia— India and China— have always had political challenges in their bilateral dealings. A semi-conductor shortage has left the global automobile industries severely bruised. Sometime in the near future it could be lithium.

Most of the future manufacturers of lithium batteries in India will have their supply chain tied up with their parent technology provider. Ingrained in the ‘technology transfer’ agreement there will be clauses that cover the technology provider also sharing its own supply chain, which would ensure continuous availability of critical raw materials including lithium for the Indian companies at globally competitive rates.

This almost ensures a client company’s permanent dependence on the parent for continued operation at a competitive rate. Not the most comfortable scenario, when your provider is a country that has often had reasons to differ with you politically and does not hesitate for a moment to leave you vulnerable and open to the vagaries of cartelised business arrangements.

Did India have any option? Why should a country with the largest technical manpower in the world have to go and ‘buy’ lithium technology knowing full well it is a material neither produced in the country nor is recyclable. On the contrary, this is a country that has been blessed with an abundance of renewable energy sources— both solar and wind. Why would India not focus on ‘green’ hydrogen, fully utilising her enormous renewable energy resources?

India also happens to be endowed with world’s fifth largest bauxite reserve for aluminium production and is ranked fourth largest in terms of zinc reserves too. Aluminium and zinc are the other two prime candidates in alternate energy storage chemistries that are being worked upon globally with signs of impending commercial viability. The country’s huge coastline assures almost unlimited availability of sodium— yet another metal at the forefront of energy storage research.

Neither from technology nor from supply chain logistics has India any established track record in lithium. It could have focussed heavily on other near-viable chemistries but chose to have its future mortgaged to lithium solutions whose universality is heavily under question and with partners whose commitments are always politically loaded.

In the words of poetry, India opted for the beaten track to the road not taken. A moment of history-making came and is lost.