Researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University have measured the cause of lithium-ion battery energy storage degradation and described their work in the journal Nature Energy.

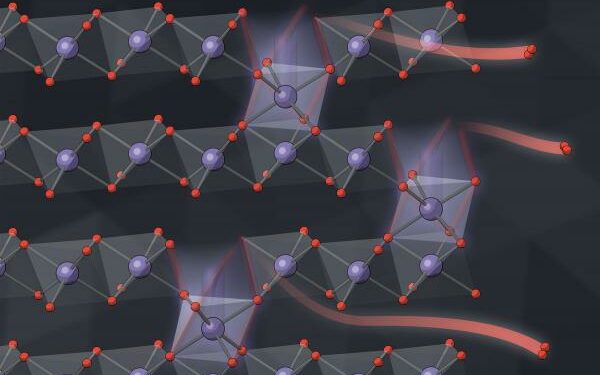

Lithium-ion batteries move lithium ions back and forth between the two electrodes, which temporarily store charge. Ideally, those ions are the only things moving in and out of the billions of nanoparticles that make up each electrode.

Researchers have known for some time that oxygen atoms leak out of the particles as lithium moves back and forth but the details have been hard to pin down because the signals from these leaks are too small to measure directly.

Peter Csernica, a Stanford PhD student who worked on the experiments with Associate Professor Will Chueh, said: “We were able to measure a very tiny degree of oxygen trickling out, ever so slowly, over hundreds of cycles. The fact that it’s so slow is also what made it hard to detect.”

“The total amount of oxygen leakage, over 500 cycles of battery charging and discharging, is 6%,” Csernica said. “That’s not such a small number, but if you try to measure the amount of oxygen that comes out during each cycle, it’s about one one-hundredth of a per cent.”

In this study, researchers measured the leakage indirectly instead, by looking at how oxygen loss modifies the chemistry and structure of the particles.

To get a closer look at what’s happening, the research team cycled batteries for different amounts of time, took them apart, and sliced the electrode nanoparticles for detailed examination at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s Advanced Light Source.

A specialised X-ray microscope scanned across the samples, making high-resolution images and probing the chemical makeup of each tiny spot. This information was combined with a computational technique called ptychography to reveal nano-scale details, measured in billionths of a metre.

Meanwhile, at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Light Source, the team shot X-rays through entire electrodes to confirm that what they were seeing at the nano-scale level was also true at a much larger scale.

Chueh, an investigator with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) at SLAC, said that, as well as oxygen leaking out, another important question is how the loss of oxygen atoms affects the material that is left behind. “Imagine the atoms in the nanoparticles are like close-packed spheres. If you keep taking oxygen atoms out, the whole thing could crash down and densify, because the structure likes to stay closely packed.”

Since this aspect of the electrode’s structure could not be directly imaged, the scientists again compared other types of experimental observations against computer models of various oxygen-loss scenarios. The results indicated that the vacancies do persist, but the material does not crash down and densify.

Chueh said: “When oxygen leaves, surrounding manganese, nickel and cobalt atoms migrate. All the atoms are dancing out of their ideal positions. This rearrangement of metal ions, along with chemical changes caused by the missing oxygen, degrades the voltage and efficiency of the battery over time.

Now, he said, “we have this scientific, bottom-up understanding” of this important source of battery degradation, which could lead to new ways of mitigating oxygen loss and its damaging effects.

Picture: Scientists at SLAC and Stanford have made detailed measurements of how oxygen seeps out of the billions of nanoparticles that make up lithium-ion battery electrodes, degrading the battery’s voltage and energy efficiency over time. In this illustration, the pairs of red spheres are escaping oxygen atoms and purple spheres are metal ions. This new understanding could lead to new ways to minimize the problem and improve battery performance. (Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory