BEST’s Asia correspondent Dipak Sen Choudhury shares his thoughts on how the Indian government is getting serious about battery waste management legislation.

The nation is on the move!

This was the slogan of the Indian government as it went to the polls in 1977. The Indian National Congress Party government of Indira Gandhi had achieved nothing. The call for the restoration of democracy by revoking emergency powers is considered by many to be a major reason for her sweeping defeat by the opposition. It will be remembered as a footnote in the history of the country as one which had taken a lot of liberty with the freedom of the people but ended up in the dumps in a very short space of time. The image of a nation on the move economically, socially, and culturally remained a promise based on unreal foundations.

Fast forward to the present and observe how this country is now planning to move ahead, thinking long-term, trying to secure the future of two of the basic pillars of life – energy and environment. The current Indian government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has an obsession. An obsession to be known as an administration that did things differently from all its predecessors. Prime Minister Modi loses no opportunity to make the point that his government is only fast-tracking things that should have been started long ago by earlier governments.

Legislation on battery waste management

Look at India’s new battery waste management legislation from the above point of view. It may be understood that this is a major attempt to kickstart a few essential activities, including technology breakthroughs that could complete a circular economy with clean sustainable energy solutions. One may call this unrealistic, but someone must mark the path ahead and hope for things to fall into place.

The country has had specific legislation before on battery waste. In 2001 the government brought in the Battery Management & Handling Rules (BMHR) for adoption across the country without exception. Highlights were:

- This legislation was solely directed at lead-acid batteries – both for automotive and industrial use

- The rules would apply to manufacturers, importers, re-conditioners, assemblers, dealers, recyclers, auctioneers, consumers, and bulk consumers. Bulk consumers meant government departments like railways, defence, and telecom

- Responsibility lay with manufacturers, importers, assemblers, and re-conditioners to ensure that used batteries were collected and exchanged for new batteries sold (excluding those sold to original equipment manufacturers and bulk consumers)

- Ensure that used batteries collected were sent only to registered recyclers

- Recycled lead is to be bought from registered recyclers only

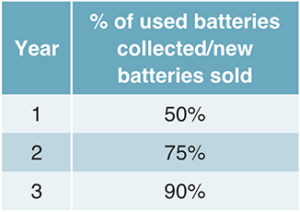

Collection targets during rules implementation:

Did the legislation deliver the objectives? The answer is a vehement no!

Throughout the country, there are thousands and thousands of unregistered recyclers with crude operations that are neither environment- nor health and safety-friendly. Their scale of operations can vary from a few hundred kilograms to a couple of tonnes of recovered lead per month. They are always offering much better rates for used lead collection compared to registered recyclers. They are neither paying for all safety and environmental protection in their operating set-ups nor are they paying the government any taxes.

Technology cost for them is zero as they use the crudest of furnaces to remelt the waste batteries. The acid is usually dumped into the municipal sewers, if available, or into the soil. Lead from users, including the so-called bulk consumers, more often than not lands up with the unregistered dealers while the capacity with the registered dealers remains idle. The bulk manufacturers and their dealers are hardly able to exhibit more than 20% of used battery collection as a percentage of new batteries sold by them. The government knows this but pleads helplessness and only pressurises the manufacturers to come up with better collection figures.

Against this, one must now examine India’s rush towards transitioning to electric vehicles (EVs). As of now, the only commercially-matured technology to serve EV demands is the lithium-ion battery (LIB). A report from the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER) stated that by 2030, India will be producing 1.4 million tonnes of LIB waste, most of it from EVs. With no source of lithium and cobalt in the country and no sign of any credible LIB recycling anywhere in the world, the sustainability of India’s EV dream looks suspect and some major incentivisation is needed to maintain the momentum of aspiration. It is from this perspective the new battery waste management legislation needs to be viewed.

What is different? The rules cover all types of batteries – lead-acid, LIB or any battery for EV, industrial or automotive applications. It explicitly prohibits the disposal of batteries through landfill or incineration.

Extended producer responsibility

The new rules on battery waste management introduce the concept of extended producer responsibility (EPR). This makes producers and importers active participants in the collection, recycling, and re-use of battery waste materials in fresh battery manufacture. To meet the various obligations of EPR, producers may engage or authorise any other entity to collect, recycle or refurbish waste batteries.

Under the new rules, the government has launched a centralised online portal that allows producers and recycling agencies to exchange complete data on collection and recovery – for complete recycling transparency.

The new rules certainly incentivise the setting up of new industries and entrepreneurship in waste battery recovery and recycling. This would be of major consequence in the LIB industry as subsequent legislative mandates make using recycled materials compulsory.

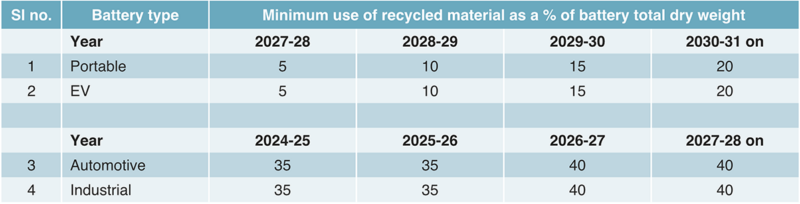

The new rules mandate the use of a defined percentage of recycled material recovered from waste batteries in new battery production. The figures look very challenging indeed, from the LIB point of view, (see Table 2).

For lead-acid the targets even for 2027-28 are by and large already achieved. However, for LIB the recycling targets for domestically produced batteries, though aspirational, may encourage investors to act seriously. Moreover, the targets set are to be reviewed every four years and may be revised to suit the state-of-art at the review point – up or down.

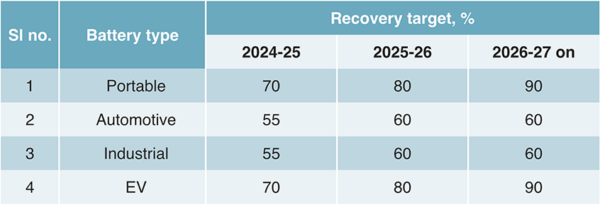

The new rules have also clearly prescribed the minimum recovery rates of various metals from waste batteries that have to be achieved by recyclers or else face financial penalties. The figures are shown in Table 3.

The expectations for LIB and other exotic chemistries are certainly stretched too far and very unlikely to be complied with. However, the expectation is to challenge the industry.

Finally, non-fulfilment of EPR will attract fines by India’s Federal Pollution Control Board and the respective state boards where the producer conducts business.

What is being achieved?

First, it is not just lead-acid but all chemistries of storage batteries that are now being brought under the umbrella of toxic battery waste management controls. Second, the responsibility is extended beyond users, manufacturers, and dealers to achieve maximum collection of waste batteries.

The concept of EPR is precisely to enlarge the scope of defining the stakeholders who collectively deliver an efficient circular economy that would, by itself, minimise the environmental damage potential of waste batteries going into the normal waste streams.

Incentives have been proposed to get the energy storage industry to shift up a gear. Perhaps these might be just the spurs that would lead to major breakthroughs in overall industrial health and economics.